About Belarus

Articles dedicated to Belarus history, Belarus politics, Belarus economy, Belarus culture and other issues and Belarus tourist destinations.The history of the Mogilev Jews

First Jews came to Mogilev (Mogilev upon Dnieper) approximately when the princes of the town started upgrading the city defenses in the early 16 century. By that time Mogilev was already in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. We know that in 1522 Mogilev taverns, wax refinery and scale tax were rented out to Mikhel Yozefovich from Berestye. It is the first Jewish name mentioned in writing in relation to Mogilev, though no Jews lived permanently in town until mid 16 century.

After Mogilev obtained Magdeburg right trade and crafts flourished and capitalism developed side by side with the Jewish community. Jews mostly became merchants, rented tax collection and offered loans at interest. Since the royal decree issued in 1577 prohibited the Jews to buy land in the city they mostly rented houses from the local residents. Orders followed one another ordering the Jews to relocate behind the rampart of the city to the bank of the Dnieper. They were not allowed to build or rent shops, saunas or breweries and sometimes were evicted from the main square on the accusations of breaking fire safety rules and unfair competition.

Sometimes the Polish kings became more flexible with the Mogilev Jews and protected them from the violations on the part of the local government or residents. With the flow of time Jews managed to bypass the prohibitions and purchased vast land lots in central Mogilev to build houses and taverns and shops. Two traditional areas of living of the Mogilev Jews were Shkolische (where the Jewish prayer school was) and Lupolovo (where leather craftsmen settled).

Historic Jewish quarter in Mogilev behind the town defences

Kahal of Mogilev was legally established in around 1626. Kahals of Eastern Belarus didn’t report to Lithuanian Vaad – they had their own Vaad called Belarusian synagogue, more or less fitting into today’s Mogilev region. The taxes collected here from individual Jewish taxpayers by 1717 were only around twice as little as those from the other Belarusian regions – an evidence of a populous Jewish community. After the takeover by the Russian Empire Mogilev gubernia kahal replaced Belarusian synagogue.

Although everyday life was majorly peaceful exacerbated only occasionally by the competition between merchants and craftsmen the traditional religious prejudices resulted in conflicts between Jews and Christians of the city. Two Cossack uprisings in Ukraine and the Russian-Polish wars of the 1650s took their death toll in southern Belarus. In 1645 a pogrom of Mogilev Jews was inspired by the chief of the city – the victims of that were the Jews taking part in the celebrations of Rosh Hashanah.

The late 18 century was a turning point for Mogilev Jews. The first partition of Rech Pospolitaya saw the Mogilev area becoming a part of the Russian Empire. Around 100 000 Jews became Russian citizens. New laws and rules were introduced: Jews were assigned to the social class of the town residents and later got the right to become merchants. In 1791 a decree was adopted that introduced the Pale of Settlement – from then on the Jews were to live in a particular area including Mogilev gubernia.

Mogilev Gubernia records have a lot of Jews

Kahals were established anew and only Mogilev residents were elected its members. In 1784 there were around 16 000 Jewish taxpayers in the gubernia, out of which about 10 per cent were merchants. They had no representation in the magistrate but in the 1860s two out of four chiefs of the magistrate court were Jewish.

The new state didn’t conscript the Jews – instead they paid a fee similar to that paid by the Russian merchants. The Russian authorities always tried to readjust the Jews so their next century was full of changes, sometimes radical and often contradictory.

Jews were prohibited to run breweries, taverns and hotels and were from time to time evicted from the villages.

Jews were being split into rich and poor by unfair taxation mode and the majority was not prospering. In 1860 about 12 300 Jews lived in Mogilev with the total population of around 25 000. They only owned over 10 per cent of the city’s industries and were mostly involved in crafts. In 1865 craftsmen and a bit later – retired military servicemen could settle beyond the Pale but that didn’t happen frequently. Another decree introduced state rabbis which were there as nominal heads of the communities – there were always informal leaders beside.

Within the last three decades Jews were being grossly discriminated against by the tsar’s government. Pogroms were inspired in the south in the 1880s, another prohibition to settle in the countryside was introduced.

My Canadian guests tracking their ancesty up to the departure point - Mogilev railway station

In 1897 Mogilev numbered 21 000+ Jews who made up to 50 per cent of the population, in 1911 – 32 600+ (around 47 per cent). In 1904 pogroms erupted in Mogilev caused by another conscript of the soldiers to take part in the Russian-Japanese war. All these developments caused massive exodus of the Jews to the US. In the last years of World War I Mogilev was the hub for landmark developments – Nicholas II abdicated in the city in February 1917.

Chasidism led by Shneur Zalman (Alter Rebbe) expanded to Mogilev and although opposition from orthodox Jews was strong the parties eventually came to some understanding. Chasids actually outnumbered orthodox Jews in Mogilev area by 1880s, but in Mogilev itself they only ran 13 prayer houses out of 38. In 1803 a wooden Chasid prayer house was erected in Shkolishe area to commemorate the release of Alter Rebbe from the Russian prison. It was later replaced with a stone building.

Mogilev Jewish cemetery (beskhaim) on Masheka Mount

In the 19 century Mogilev had future trade unions - khevre – communities of mutual help that united workers of a certain workshop.

The Jews of Mogilev were involved in large-scale wheat, timber and banking operations. In the early 20 century Mogilev became a major printing ground for books which was mostly because of Jews. The 19th century printing houses ran by them majored mainly in religious literature but then switched into Russian speaking products. The ancestor of Marc Chagall ran the first cab line in Mogilev since 1911.

Jews also ran most of the town’s hotels – in 1914 19 hotels belonged to them. By the early 20 century they came to own 90 per cent of the central stone buildings in Mogilev. Normally, their first floors also house Jewish–run shops.

The date of construction of the first synagogue in Mogilev is unknown. By the late 17 century the Jewish community was allowed to have two schools and synagogues in Shkolishe and Lupolovo. Dubrovenka synagogue was first mentioned in 1820. The largest synagogue in Mogilev dates back to the 1850s. A disused building of the palace of a Catholic archbishop was purchased and renovated by merchant Zukermann. Another old synagogue building probably belonged to the merchant community, hence the name “Merchant”.

The "Merchant" synagogue in Mogilev

Several dozen synagogues and prayer houses in Mogilev were closed by the 1930s. The grandest of them, a two-floor building, was dismantled in Shkolishe area in the same period.

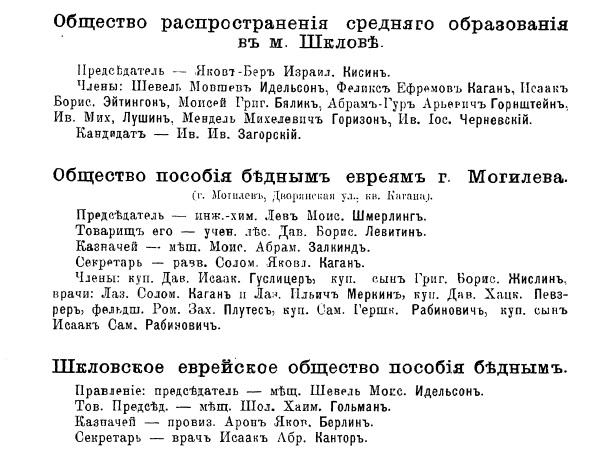

Before 1917 revolution Jewish charities (hospitals, cheap canteens and aid groups) were multiple and active in Mogilev, mostly by the grace of merchants.

The 1917 Revolution that destroyed the Russian Empire and established the USSR saw Jews dividing into pro-Communists and anti-Communists. The poorer ones advocated equality and free education in the first line, the richer ones hated to see their power go along with their properties. Since the Communists eradicated the tsar’s officials and therefore positively lacked educated labour force Jewish staff was on demand. Many Jews entered Soviet executive offices, including in Mogilev. Many of them were not just talented doctors or musicians, but also farmers and engineers and made an input into the creation of the modern industries of Mogilev.

After its formal liquidation in 1918 the Jewish community of Mogilev operated illegally. Communist Party established Jewish sections to promote their ideals among the Yiddish speaking circles; their personnel was destroyed in the Stalin’s repressions of the 1930s. Hebrew was outlawed at once, and by and by so were all the religious or national organizations.

Many people in Mogilev were badly deprived in the 1920s: former priests or businessmen on top of losing their properties and capitals also lot civilian rights which exacerbated their existence. In Mogilev in 1924 over 16 500 Jews resided (40 per cent of the total).

In 1937-1938 many Jewish priests in Mogilev were arrested on false accusations and executed as a part of the global program of Stalin’s purges. 1939 census revealed around 20 000 Jews (about 20 per cent of the population) though the number of Jews might have been higher.

Mogilev Jewish ghetto was established after the occupation of the city in July 1941. The defence of Mogilev was in place for 3 weeks and while many Jewish men were fighting in the Red Army a lot of civilians managed to flee eastwards. That makes the estimation of the number of Jews in the Nazi-occupied Mogilev impossible.

The Jewish community member explains restoration plans to a Canadian visitor

Discriminating regulations against the Jews were immediately in place once the city fell. Curfew was introduced and numerous bans and the mandatory yellow six-point stars on the outerwear. Locals were prohibited to have any contacts with the Jews and specifically to supply them with any products. Registration conducted by the judenrat in early August 1941 listed 6 437 persons with many Jews hiding to avoid getting on any lists.

First category Jews (80 men) capable of heading resistance activities were murdered in August. The second category was to be isolated within 24 hours into a dedicated area – a ghetto in Grazhdanskaya Street. Jews from Vorotynshina and Knyazhitsy were also forced there.

In September 1941 the ghetto was relocated to the Dubrovenka river bank and was limited by Bykhov market and Vilenskaya Street. 108 Jews from Selets were cramped into several buildings in Vilenskaya Street. The Mogilev Jewish ghetto was guarded by gendarmes and Belarusian policemen. Prisoners were later forced to build a wooden fence around the area with the writings: “Jewish living quarters. Non-Jews are not allowed”. Judenrat was ordered to establish 15-strong Jewish police force.

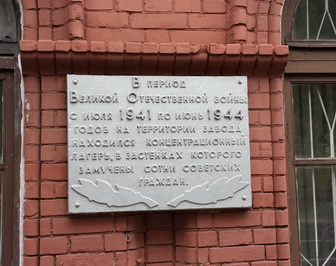

Strommashina factory ghetto plaque

Living mode in the ghetto was extremely harsh with 40-60 persons sharing living space of a house. Able-bodied prisoners were forced to work, normally humiliating jobs, food was not provided. People were killed on any reason and with no reason at all. Thus 113 Jews were killed already during the relocation for trying “to sabotage the removal”.

October 1941 saw the Nazi performing 2 Aktions against Dubrovenka ghetto. On 2-3 October 2273 Jews were shot in Mashekovo Jewish cemetery by the police and collaborators. On 19 October 1941 3726 Jews were convoyed presumably to Kazimirovka and shot. It is so far unknown when 4800 Jews were executed near Polynkovichy village. Executions in Mogilev ghetto involved gas vans. The empty ghetto buildings were then thoroughly searched for clothing, jewelry or house utilities.

The second stage of the Jewish community destruction was to see the destruction of the third category Jews – craftsmen – whose labour was badly required by the Nazi. Bootmakers, blacksmiths, carpenters, tinsmiths, glassmakers and painters were forced into a factory area (now Strommashina) with restricted access.

Mogilev Jewish cemetery today

Somewhat over a 1000 Jews were taken here in late September. Many groups of Jews were brought from other locations to be killed in the factory area while the prisoners there were involved in forced labour activities. Harsh regime and extremely poor nourishment resulted in dozens of daily deaths, also caused by epidemics, with every Sunday an execution taking place. The efforts of a resistance group that existed at the factory helped 73 prisoners to escape.

The ghetto was extended by October 1941. In December 180 Jewish prisoners were killed accused of sabotage. Around 400 Slonim Jews were taken from Slonim to the camp on 26 May 1942. One of the Aktions alone claimed 4000 lives in 1942. By September 1943 about 500 Jews remained in the factory ghetto of which 276 Jews were then taken to Minsk and later – to Majdanek. After the Jews had been killed mixed families became the main target.

In autumn 1943 the Nazi extracted human remains from the graves in Polykovichy, Novopashkovo and Kazimirovka villages and incinerated them. Approximate death toll of the Mogilev Jews is 12 000 people. Most of the execution sites of the Jews have been marked with plaques or memorials.

If you wish to take an ancestral trip to Mogilev do not hesitate to contact your private Minsk guide.

Flying over the Mogilev Jewish cemetery

|

|

Featured

Applying at their local Belarus Consulate, the citizens of migration-secure states (e.g. the USA, Canada, Japan and others) can obtain a short-term...

The form of application for a visa to Belarus has become digital and you can save and send it as a PDF file. It is only a 2-page document that is available...

Quite a number of things, as a matter of fact. Let’s examine a typical case from my travel agent’s past with a traveler landing in Minsk Airport (MSQ) and applying for a visa...

People, who want to travel to Belarus to see a friend, take care of the grave of a relative, take part in the court hearings, etc. need to apply for a private visa...

This article covers field family research in Belarus that in most cases comes after dealing with the State archives of Belarus and genealogical research.

A plastic card is a fine thing, no doubt, but there have been a number of cases when the ATM displayed ERROR, or required a PIN code...

While most tourists agree that Belarus is not the country for grand shopping, there are still some things that can be brought back as souvenirs...